Level: Basic

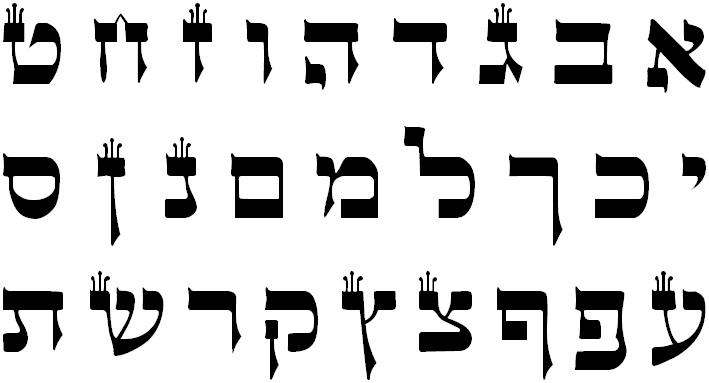

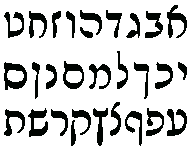

The Hebrew and Yiddish languages use a different alphabet than English. The picture below illustrates the Hebrew alphabet, in Hebrew alphabetical order. Note that Hebrew is written from right to left, rather than left to right as in English, so Alef (א) is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet and Tav (ת) is the last. The Hebrew alphabet is often called the "alefbet," because of its first two letters.

Table 1: The Hebrew Alphabet

If this sounds like Greek to you, you're not far off! Many letters in the Greek alphabet have similar names and occur in the same order (though they don't look anything alike!): Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta ... Zeta ... Theta, Iota, Kappa, Lambda, Mu, Nu ... Pi ... Rho, Sigma Tau.

The "Kh" and the "Ch" are pronounced as in German or Scottish, a throat clearing noise, not as the "ch" in "chair."

Note that there are two versions of some letters. Kaf/Khaf (כ ך), Mem (מ ם), Nun(נ ן), Pei/Fei (פ ף) and Tzadei (צ ץ). The second version, usually extending below the baseline of the letter, is the "final" form of the letter, used only at the end (the left side) of a word. When a letter with a second pronunciation (discussed along with Table 3 below) appears at the end of a word, it almost always takes the second pronunciation, so I have identified the final forms of Kaf and Pei above with their second pronunciation.

Like most early Semitic alphabetic writing systems, the alefbet has no vowels. People who are fluent in the language do not need vowels to read Hebrew (Cn y rd ths?), and most things written in Hebrew in Israel are written without vowels.

However, as Hebrew literacy declined, particularly after the Romans expelled the Jews from Israel, the rabbis recognized the need for aids to pronunciation, so they developed a system of dots and dashes called nikkud (points). These dots and dashes are written above, below or inside the letter, in ways that do not alter the spacing of the line. Texts containing these markings are often referred to as "pointed" text.

Illustration 1: Pointed Text

Illustration 1 is an example of pointed text. Nikkud are shown in blue for emphasis (they would normally be the same color as the consonants). In Sephardic pronunciation (which is what most people use today), this line would be pronounced: V'ahavtah l'reyahkhah kamokhah. (And you shall love your neighbor as yourself. Leviticus 19:18).

Table 2: Vowel Points

Table 2: Vowel Points

Most nikkud are used to indicate vowels. Table 2 illustrates the vowel points, along with their pronunciations. Pronunciations are approximate; I have heard quite a bit of variation in vowel pronunciation.

Vowel points are shown in blue. The letter Alef (א), shown in red, is used to illustrate the position of the points relative to the consonants. The letters shown in purple (Vavs ו and Yods י) are technically consonants and would appear in unpointed texts, but they are part of the vowel in this context.

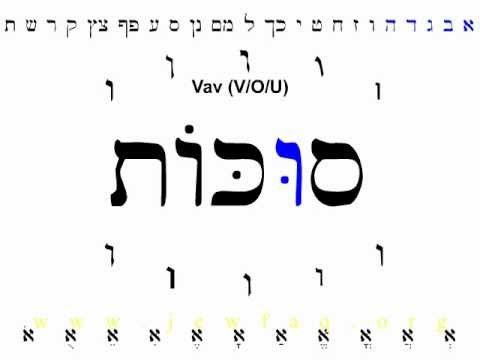

Vav (ו), usually a consonant pronounced as a "v," is sometimes a vowel pronounced "o" as in "alone" (transliterated "o") or "oo" as in "moon" (transliterated "u" or "oo"). When a Vav has a dot on top, it's usually pronounced "o", but sometimes "vo". When it has a dot in the middle, it's usually pronounced "u", but sometimes"v". So how do you know which way to pronounce these Vav forms? There are simple rules:

ha'olam

b'mitz'votav

v'tzivanu

Three common prayer words, found in just about every blessing, illustrate these rules: ha'olam, b'mitz'votav and v'tzivanu. Ha'olam pronounces the Vav with a dot on top as you would expect: as an "o" sound. B'mitz'votav has a Vav with a dot on top, but it's pronounced "vo." You have to pronounce the "v" because the consonant before it has its own vowel (albeit a silent one, the vertical dots) and a Vav vowel can't follow another vowel. Note that the consonant before the Vav in ha'olam has no vowel (although the consonant is silent). In v'tzivanu, the Vav in the middle of the word has a vowel of its own underneath (looks like a T), so it is a consonant and is pronounced as a "v" sound. The Vav with a dot in the middle at the end of the word is pronounced as you would expect, as a "u" sound, because it has no vowel and the consonant before it has none.

Table 3:

Other Nikkud

There are a few other nikkud, illustrated in Table 3.

The dot that appears in the center of some letters (we saw it above in the Vav) is called a dagesh. It can appear in just about any letter in Hebrew. With most letters, the dagesh does not significantly affect pronunciation of the letter; it simply marks a split between syllables, where the letter is pronounced both at the end of the first syllable and the beginning of the second. With the letters Beit (ב), Kaf (כ) and Pei (פ), however, the dagesh indicates that the letter should be pronounced with its hard sound (b, k, p) rather than its soft sound (v, kh, f). See Table 3. In Ashkenazic pronunciation (the pronunciation used by many Orthodox Jews and by many older Jews), Tav (ת) also has a soft sound, and is pronounced as an "s" when it does not have a dagesh. That's why you may have heard people speak of the female coming-of-age ceremony as a bas mitzvah instead of a bat mitzvah. The ritual of circumcision is most commonly referred to as a bris. Both words end with an undotted Tav. With Vav, as we saw above, the dagesh usually (but not always) indicates a "u" sound instead of the usual "v" sound.

Shin (ש) is pronounced "sh" when it has a dot over the right branch and "s" when it has a dot over the left branch. The letter is called Sin when the dot appears on the left, and functions as a completely separate letter of the alphabet, even to the extent of appearing in a separate chapter in many dictionaries!

![]() The dot over the Shin or Sin can sometimes merge into an "o" vowel next to it, so that an "osh" sound or a

"so" sound usually have just one dot instead of two next to each other. The best-known example of this is the

name Moshe (Moses), which has an "o" vowel followed by a Shin and the dots combine so there is no visible

vowel on the Mem (מ).

The dot over the Shin or Sin can sometimes merge into an "o" vowel next to it, so that an "osh" sound or a

"so" sound usually have just one dot instead of two next to each other. The best-known example of this is the

name Moshe (Moses), which has an "o" vowel followed by a Shin and the dots combine so there is no visible

vowel on the Mem (מ).

The style of writing illustrated above is the one most commonly seen in Hebrew books. It is referred to as block print, square script or sometimes Assyrian script. But there are several other styles of writing these letters, and some of them can be hard to recognize as the block print letter, just as some letters in English cursive can be hard to recognize for those unfamiliar with that style. In the example images below, I have kept the letters in the same layout as the alphabet at the top of the page to make the letters easier to identify.

Table 4: STA"M Font

For sacred documents, such as torah scrolls or the scrolls inside tefillin and mezuzot, there is a special writing style with "crowns" (crows-foot-like marks coming up from the top) on many of the letters. This style of writing is known as STA"M, an acronym of Sifrei Torah, Tefillin and Mezuzot, which is where you will see that style of writing. Table 4 illustrates this style of writing with a font. When this style is used in a sacred document, some of the letters may be widened significantly to make the text line up on both the right and the left, similar to the way English text is justified by adding space between words or letters. Some letters are never widened to avoid confusing them with others (a wide Vav would look like a Reish; a wide Nun would look like a Kaf), but distinctive letters like Lamed are commonly widened.

For more information about the STA"M alphabet, including illustrations and relevant rules, see Hebrew Alphabet used in writing STA"M.

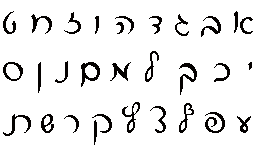

Table 5: Hebrew Cursive Font

There is another style commonly used when writing Hebrew by hand, often referred to as Hebrew cursive or Hebrew manuscript. Table 5 shows the complete Hebrew alphabet in a font that emulates Hebrew cursive. People in Israel don't hand-write the fancy block text at the top (though many American Hebrew school students do); Israelis use this cursive style. You will also see this cursive style used for the Hebrew name in Jewish birth records that you may see doing genealogy.

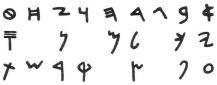

Table 6: Rashi Script

Another style is used in certain texts, particularly the Talmud, to distinguish the body of the text from commentary explaining the text. This style is known as Rashi Script, in honor of Rashi, the greatest commentator on the Torah and the Talmud. Rashi himself did not use this script; it is only named in his honor. Table 6 shows the complete Hebrew alphabet in a Rashi Script font.

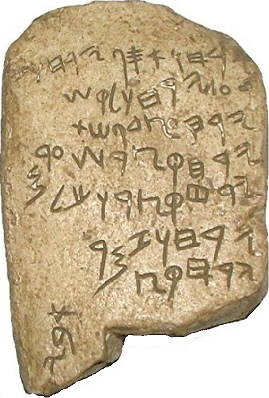

Table 7: K'tav Ivri (Paleo-Hebrew)

As mentioned above, the Hebrew alphabet that we use today is referred to as Assyrian Script (in Hebrew, K'tav Ashuri). But there was once another way of writing the alphabet that the rabbis called K'tav Ivri, which means "Hebrew Script." Scholars call it Paleo-Hebrew or Proto-Hebrew. It is quite similar to the ancient Phoenician writing. There are no final forms of letters in K'tav Ivri, as there are for some letters in the Hebrew scripts we use today, which is why there aren't as many letters here. I left gaps in Table 7 where the final versions of letters are found in the other examples to make it easier for you to see which letter is which. You will see examples of K'tav Ivri that look somewhat different than the letters above. Remember that all text in those ancient times was written by hand, so the appearance varied from person to person and changed over time. I made my example above from a font that called it Paleo-Hebrew, but I have seen many different versions in various places online, aned I have seen this font identified as Phoenician, which is not surprising because the alphabets are related.

Gezer Calendar

Image from

Rabbi

Anthony Manning

Transliterated into a modern Hebrew font:

Many examples of this ancient way of writing the Hebrew alphabet have been found by archaeologists: on coins and other artifacts. One of the oldest such examples is the "Gezer Calendar" found near Jerusalem and dated to around the time of King Solomon. The "calendar" is more of an agricultural schedule, possibly written by a schoolboy! Some evidence that it was written by a schoolboy: the second line of text begins on the first row and the word at the end of that row wraps around to the second row (the second row should probably be ירחוזרעירחולקש). The rest of the rows all start where you would expect.

It has been translated as:

Two months of harvesting [Tishri, Cheshvan]

Two months of sowing [Kislev, Tevet]

Two months late planting [Shevat, Adar]

A month cutting flax [Nissan]

A month reaping barley [Iyar]

A month reaping and measuring [Sivan]

Two months pruning [Tammuz, Av]

One month summer fruit [Elul]

followed by the author's name (Aby) written vertically

The similarity of the Hebrew and Phoenician alphabets is so strong that scholars don't even agree on whether this Gezer Calendar is Hebrew or Phoenician! The date of the tablet is not certain, the region changed hands around that time, and there's nothing specifically Jewish about this text (the Hebrew month names in brackets are my own additions). But even if it's not actually Hebrew, it's very similar to what ancient Hebrew looked like.

The rabbis of the Talmudic period were well aware of this ancient K'tav Ivri, and they raised the question whether the Torah was originally given in K'tav Ivri or K'tav Ashuri. A variety of opinions are expressed in the Talmud at Sanhedrin 21b-22a: one opinion states that the Torah was originally given in K'tav Ivri, but was changed to K'tav Ashuri in the days of Ezra, during the Babylonian Exile (the Babylonians used K'tav Ashuri, and consequently the Jews in exile used it in the same way that we transliterate Hebrew into the Roman alphabet). Another opinion says that the Torah was written in K'tav Ashuri, but that holy script was denied the people when they sinned and was replaced with another one; when the people repented, the K'tav Ashuri was restored. A third opinion states that the Torah was always in K'tav Ashuri.

The traditional religious consensus is that the Torah was given in K'tav Ashuri, because the Talmud makes other references that don't make sense in K'tav Ivri. The Talmud talks about final forms of letters in the original Torah, but K'tav Ivri doesn't have final forms. It talks about the center of the Samekh (ס) and the Final Mem (ם) miraculously floating when the Ten Commandments were carved all the way through the tablets, but there is no Final Mem in K'tav Ivri, and neither Samekh nor Mem would have a floating center in K'tav Ivri as they do in K'tav Ashuri.

All authorities maintain that today, the only holy script is K'tav Ashuri. Any Torah scrolls, tefillin or mezuzot must be written in K'tav Ashuri, and specifically in a style of K'tav Ashuri known as STA"M, discussed above. Today, K'tav Ivri is mostly used to make text look old-fashioned, like calling a bar Ye Olde Taverne.

K'tav Ivri is understood to be in the nature of a font, like Rashi script, rather than in the nature of a different alphabet, like Greek, Cyrillic or Roman. The names of the letters, the order of the letters, and the numerical value of the letters are apparently the same in both K'tav Ashuri and K'tav Ivri; thus, any religious significance that would be found in the numerical value of words or the sequence of the alphabet is the same in both scripts. The only difference is the appearance.

The process of writing Hebrew words in the Roman (English) alphabet is known as transliteration. Transliteration is more an art than a science, and opinions on the correct way to transliterate words vary widely. This is why the Jewish festival of lights (in Hebrew, Cheit-Nun-Kaf-Hei, חנכה) is spelled Chanukah, Hanukkah, and many other interesting ways. Each spelling has a legitimate phonetic and orthographic basis; none is right or wrong.

The Roman letters in Table 1 above are probably the most common transliterations of those consonants in America, except that Khaf (final or without the dagesh, כ ך) is sometimes transliterated as ch. I prefer to use kh to distinguish between Khaf and Cheit (ח), but that's just my preference. Fei (פ) is often transliterated as ph, which I like because it makes it clear that this is the same letter as Pei (פּּ). That's also part of why I like kh for khaf, because kaf (כּ) is usually transliterated as k, not c.

It's the vowels that make transliteration particularly complicated. Americans pronounce the English vowels differently (local accents), and Americans don't all pronounce Hebrew in quite the same way (certainly not the same way they do in Israel), so it's hard to write the Hebrew words in English letters that Americans would pronounce in a recognizable way. There are also different opinions about how to represent the schwa vowels. Do we use an apostrophe (') or a vowel that sounds close (usually an "e")? And do we use a hyphen to separate prefixes like ha (which is the definite article "the" in Hebrew)? Transliteration from different sources could be hard to recognize as the same original Hebrew text!

Table 8: Values of Hebrew Letters

Table 8: Values of Hebrew Letters

Each letter in the alefbet has a numerical value. These values can be used as numerals, similar to the way Romans used some of their letters (I, V, X, L, C, D, M) as numerals. Table 8 shows each letter with its corresponding numerical value. Note that final letters have the same value as their non-final counterparts.

The numerical value of a word is determined by adding up the values of each letter. The order of the letters is irrelevant to their value: the number 11 could be written as Yod-Alef (יא), Alef-Yod (אי), Hei-Vav (הו), Dalet- Dalet-Gimel (דדג) or many other ways. Ordinarily, however, numbers are written with the fewest possible letters and with the largest numeral first (that is, to the right). The number 11 would be written Yod-Alef (יא) (with the Yod on the right, because Hebrew is written right-to-left), the number 12 would be Yod-Beit (יב), the number 21 would be Kaf-Alef (כא), the number 611 would be Tav-Reish-Yod-Alef (תריא), etc. The only significant exception to this pattern is the numbers 15 and 16, which if rendered as 10+5 or 10+6 would be a name of G-d, so they are normally written Teit-Vav (טו) (9+6) and Teit-Zayin (טז) (9+7).

Because every letter of the alphabet has a numerical value, every word also has a numerical value. For example, the word Torah (Tav-Vav-Reish-Hei, תורה) has the numerical value 611 (400+6+200+5). There is an entire discipline of Jewish mysticism known as Gematria that is devoted to finding hidden meanings in the numerical values of words. For example, the number 18 is very significant, because it is the numerical value of the word Chai (חי), meaning life or living. Donations to Jewish charities are routinely made in denominations of 18 for that reason ($18, $36, $180 and $360 are quite common). It is often very confusing to gentile charities when Jews make donations in these kinds of numbers!

Some have suggested that the final forms of the letters Kaf (ך), Mem (ם), Nun (ן), Pei (ף) and Tzadei (ץ) have the numerical values of 500, 600, 700, 800 and 900, providing a numerical system that could easily render numbers up to 1000. However, there does not appear to be any basis for that interpretation in Jewish tradition. A cursory glance at any Jewish tombstone will show that these letters are not normally used that way: the year 5766 (2005-2006) is written Tav-Shin-Samekh-Vav (תשסו, 400+300+60+6; the 5000 is assumed), not Final Nun-Samekh-Vav (ןסו, 700+60+6). Indeed, writing it in that way would look absurd to anyone familiar with Hebrew, because a final letter should never appear at the beginning of a word! But even where numerology is used only to determine the numerical values of words, you will not find examples in Jewish tradition of final letters being given different values. For example, in traditional sources, the numerical value of one name of G-d that ends in Final Mem is 86, not 646.

In the early days of the World Wide Web, I received several e-mails pointing out that the numerical value of Vav (ו, often transliterated as W) is 6, and therefore WWW (ווו) has the numerical value of 666! The Internet, they say, is the number of the beast! It's an amusing notion, but Hebrew numbers just don't work that way. In Hebrew numerals, the position of the letter/digit is irrelevant; the letters are simply added up to determine the value. To say that ווו is six hundred and sixty-six would be like saying that the Roman numeral III is one hundred and eleven. The numerical value of ווו in Hebrew would be 6+6+6=18, so WWW is equivalent to life! (It is also worth noting that the significance of the number 666 is a part of Christian numerology, and has no basis that I know of in Jewish thought).

While we're on the subject of bad numbers, it is worth noting that the number 13 is not a bad number in Jewish tradition or numerology. Normally written as Yod-Gimel (יג), 13 is the numerical value of the word ahava (love, Alef-Hei-Beit-Hei, אהבה) and of echad (one, as in the daily prayer declaration, G-d is One!, Alef-Cheit-Dalet, אחד). Thirteen is the age of responsibility, when a boy becomes bar mitzvah. We call upon G-d's mercy by reciting his Thirteen Attributes of Mercy, found in Exodus 34:6-7. Rambam summed up Jewish beliefs in Thirteen Principles.

Hebrew characters are included in Unicode, the international standard for encoding text, and have been there since the early 1990s. The Hebrew Unicode block is located at U+591 to U+5F4. It includes consonants for Hebrew and Yiddish (U+5D0 to U+5F2), vowel points (U+5B0 to U+5BB), trop points (U+591 to U+5AE) and some punctuation and other marks used in Hebrew. Many fonts (but not all!) have a built-in Hebrew characters for these unicode values. In my Windows 10 computer, Hebrew characters exist for these codes in the common built-in fonts Times New Roman, Arial, Courier New and Calibri, but not in Century Gothic or Comic Sans MS. In Windows, you can see these characters using the Windows Character Map tool. But even if your font has Hebrew characters, the font or your word processor may not lay the text out properly, may not position the characters from right to left and may not position the nikkud correctly.

On this site, I handle Hebrew characters using a Google font that is downloaded when you load the page, Noto Serif Hebrew. This font seems to handle the text the way I want it most of the time. That font can be downloaded and installed on your cocmputer for use in word processors and sduch. If you want to see if your computer is handling the Hebrew characters properly for some basic standard fonts, this page displays Hebrew characters in some standard fonts so you can see what you're getting.

But even if you have this Unicode Hebrew support, persuading your computer to type these characters can be a bit of a challenge! This page includes a JavaScript tool that will help you type Hebrew, if you have Hebrew support. The results of that script can be copied and pasted into your word processor, if it supports Hebrew characters. Depending on your word processor, you may need to reverse the results for them to appear properly. The page can reverse them for you. Feel free to download that page and use it on your own computer. The scripts you need to run it are all in the file.

If you are serious about writing a significant amount of text in Hebrew, you will need a proper Hebrew word processor. I have used DavkaWriter, from Davka Software. DavkaWriter comes with many attractive Hebrew fonts including both consonants and vowels that will map to your keyboard in an intuitive phonetic way or in the standard Israeli keyboard format. It is very easy to switch between Hebrew and English within a document. DavkaWriter even comes with little stickers to put on the keys of your keyboard so you can learn their keyboard mappings, and an onscreen display shows you their keyboard mappings. It contains the full text of the Hebrew Bible, two different prayer books and some commentary, all in Hebrew. Davka also has a lot of fonts available, as well as a lot of other Hebrew and Judaic software. For mobile devices, there are a number of apps, many of them free, that will allow you to type Hebrew characters.

Hebrew Alphabet Playlist

Hebrew Alphabet Playlist Hebrew Alphabet - Just the Letters

Hebrew Alphabet - Just the Letters Hebrew Language: Root Words

Hebrew Language: Root Words Yiddish Language and Culture

Yiddish Language and Culture