Level: Basic

- Jewish genealogy isn't easy, but it isn't as hard as you might think

- Many things you "know" about Jewish genealogy aren't true

- With a systematic approach, you should be able to trace back to your immigrant ancestors or farther

In the past, most Jews were not as interested in documenting their pedigrees as gentiles were. In recent

years, however, genealogy has become a popular hobby for both Jews and gentiles, as evidenced by popular

television shows like Finding Your Roots and

Who Do You Think You Are?. Jewish genealogical

research has also taken on an added importance for those moving to Israel,

because the increasingly strict Israeli rabbinate requires higher levels of proof of Jewish status. See the

2008 article in the New York Times magazine,

"How Do You Prove You're a

Jew?" by Gershom Gorenberg.

I'm no expert on genealogy, but I have had a great deal of success over the last several years researching my

family tree and helping others research theirs. From three Jewish parents, I have identified 22 of 24

possible 2nd-great-grandparents born in the mid 1800s; 24 out of 48 possible 3rd-great-grandparents born in

the early 1800s, and a few ancestors back to the early 1700s. This page will pass along some of the benefit

of my experience.

☰ Debunking Jewish Genealogy Myths

Many people believe that Jewish genealogy is not possible because no one in the

family knows anything, names were changed at Ellis Island, records were

destroyed by Hitler, towns don't exist anymore, and so forth. The reality is,

these assumptions are not entirely true, and you can probably trace your family

tree one or two generations farther than you think you can. Let's look at some

of these genealogy myths.

- No one in my family knows anything

- Have you actually asked them? You might be surprised by what people know.

Jews don't talk much about their family history, but that doesn't mean they

don't know anything. When I had to do a genealogy project for school in 4th

grade, my father told me the names of his grandparents, and I assumed that was

all he knew. As an adult, I had done quite a bit of research on my family tree

before I found out that my father knew much more: he had compiled a family tree

as a bar mitzvah project in the 1950s,

while many of the older relatives were still living. His tree included all

eight of his great-grandparents, some of his 2nd-great-grandparents and dozens

of aunts and uncles and cousins. In addition, my father's brother and cousin

had done ongoing research that I did not know about until long after I had

started my work.

- The name was changed at Ellis Island

- This is one of the most widespread myths of genealogy, and many people

lovingly cling to their family's quirky name-change stories even when

confronted with the facts. Sorry to disappoint you, but nobody's name was

changed at Ellis Island. Lists of passengers were compiled at the port of

departure based on the name found in the ticket. The names given upon arrival

in the United States had to match the name on the passenger list and on the

ticket. But even if the name were recorded incorrectly at Ellis Island, it

wouldn't matter, because you didn't have to use the name that was recorded at

Ellis Island. In the days before social security cards, drivers' licenses,

credit cards and all the other identification we rely on today, it was

perfectly legal to change your name -- both first and last name -- any time you

wanted as long as you didn't do it to avoid payment of your debts. And that's

the bad news: your family member's name may have changed several times both

before and after Ellis Island. My great-great-grandmother was listed on

immigration records in 1883 as Babette Reich, but died in 1900 as Bertha Rich.

Her son Heinrich became Henry in America. My grandmother was identified as Lee

Moldow on her American marriage certificate, but she shows up in early census

records as Lena Moldofsky and in an Ellis Island record as Bluma Moldansky. Her

brother shows up as Irving, Isidore and Isak. Tracking down family information

when the names may have changed repeatedly can be quite challenging.

- The records were destroyed by Hitler; the towns don't exist anymore

-

During

the Holocaust, the Nazis killed people, burned synagogues and wiped out towns,

but they did not destroy records. Quite the contrary, they carefully preserved

synagogue records of births, deaths and marriages back to the 1840s... so they

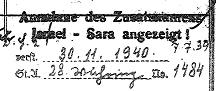

could identify Jews for extermination. See this puzzling stamp, dated November

30, 1940, on my great-grandfather's 1878 Vienna Jewish birth record: Annahme

des Zusatznamens Israel-Sara angezeigt (assume of the other names that

Jew-Jewess is indicated). What is the meaning of this cryptic message? It is a

reminder to those inspecting the records that they should assume everyone

mentioned on the page is Jewish -- not just the parents and children, but also

the rabbi,

mohel, midwife, witnesses, and so forth.

Many of these European records, diligently preserved by the Nazis, are indexed

by JewishGen

or are available from the Family

History Library of the Latter Day Saints (Mormons). Both of these resources

are discussed below.

During

the Holocaust, the Nazis killed people, burned synagogues and wiped out towns,

but they did not destroy records. Quite the contrary, they carefully preserved

synagogue records of births, deaths and marriages back to the 1840s... so they

could identify Jews for extermination. See this puzzling stamp, dated November

30, 1940, on my great-grandfather's 1878 Vienna Jewish birth record: Annahme

des Zusatznamens Israel-Sara angezeigt (assume of the other names that

Jew-Jewess is indicated). What is the meaning of this cryptic message? It is a

reminder to those inspecting the records that they should assume everyone

mentioned on the page is Jewish -- not just the parents and children, but also

the rabbi,

mohel, midwife, witnesses, and so forth.

Many of these European records, diligently preserved by the Nazis, are indexed

by JewishGen

or are available from the Family

History Library of the Latter Day Saints (Mormons). Both of these resources

are discussed below.

☰ Setting Proper Expectations

So we see that Jewish genealogy is not as impossible as we might think. But it's not easy either. You are not

likely to simply log onto Ancestry (or even

JewishGen) and find a comprehensive tree listing your family back

300 years, or Google a book listing all descendants of an ancestor 400 years ago, as some gentiles do. But

you should be able to trace your family tree back to the point of immigration (usually between 1860 and

1910), and some American records (marriage, death) may give you the names of the parents of those immigrants.

Finding records from overseas is a bit more challenging, partly because of the language barrier (most Jews

didn't come from English-speaking countries) and partly because of the scattershot availability of those

records. They weren't destroyed by Nazis, but they may not be readily available online.

Another challenge is that Jews did not have permanent family names as we know them until around 1800 and

later in some places. My Romanian 2nd-great-grandmother (born 1864) had a brother who used a different

surname than her father's. It can be hard to tell if the David ben (son of) Joseph in a record is the one you

wanted.

Keep in mind as you do your research that not everything you find will be completely accurate. We live in a

society today where every aspect of our lives is so thoroughly documented that it is often hard for us to

understand: our ancestors didn't always know their own date of birth let alone their parents'. They may have

known the Hebrew date of birth, which moves around the secular calendar, or the date of birth on the Julian

calendar that was used in the Russian Empire until 1918. They didn't necessarily know their mother's maiden

name. Even if they knew these things, the information may not have been recorded accurately or transcribed

accurately for online sources.

☰ Step-by-Step: Recommendations for Genealogy Research

This is the approach I have taken in researching my own family trees and also helping other people. It works

for me. If you're not as obsessive-compulsive as I am, you may find it easier to simply throw some names into

an index and see what sticks. My approach is intended to work from the present back, although you may find

that you need to skip around and revisit some of these steps as you go along. Some of these sources are

available free on the Internet; some require only free registration; others require subscriptions or fees. I

will identify fee sites where necessary.

I would strongly suggest that you track not just your ancestors, but also all of their siblings. The names of

siblings will help you locate and verify other records: if the family changed names between censuses (or if

the census taker spelled the name incorrectly), you can be sure it is the right family if there are the right

number of people with the same or similar given names and ages. In fact, you may find it very rewarding to

track down all of the descendants of your ancestors. You'll get a lot more results, and you'll end up finding

cousins you never knew instead of European gravestones! I've been tracing one branch of my family tree for

about 25 years on and off, and I've tracked it back to a 4th-great-grandfather born in Hungary in 1785. I'm

rather proud of that, but I'm more proud of having identified more than 1,000 of his descendants in Hungary,

the United States and South America!

- 1. Talk to everyone in your family

- I'm not going to belabor this rather obvious point any more than necessary, but suffice it to say that,

as I said above, your family members may know more than you realize. It's a lot easier to find documents

confirming what they know and building on it than it is to start from scratch. Talk to them repeatedly in the

course of your research: you may find that some of what you discover triggers their memories. I was looking

at marriage indexes in New York for my grandparents and found two possibilities. I asked my mother when her

parents' anniversary was, and she insisted that she had no idea. "October or April?" I asked. "Oh! Yes,

April, of course!"

- 2. Social Security Death Index (SSDI)

- This provides valuable information about most people who died in the United States between 1960 and

February 2014 and many others who died as early as 1937. If they had a Social Security Number and died in the

United States, they should be in there, though many (especially women) did not have a Social Security Number

until at least the 1960s. The SSDI gives their dates of birth and death, their last known residence, and the

place where they were living when they got their social security number. You can search this for free (with

registration) on FamilySearch.

Ancestry.com (a subscription site) also has a

Social Security Applications and Claims

Index, which often gives incredibly useful information from Social Security records: date and place of

birth, father's name, mother's maiden name, and name changes (particularly useful for women who may have

remarried), but it does not include full information about everyone with a Social Security Number.

- 3. Census Records

- Censuses in the United States have been taken every ten years from 1790 to the present. Census records

from 1790 to 1950 (except 1890) are available online. Starting in 1850, they identify all members of the

household (earlier years just listed the head of household and a count of househould members in various

categories), and starting in 1880, they specify the relationship of each household member to the head of

household (wife, child, mother-in-law, or just boarder or servant). Censuses are available for free from

FamilySearch, the LDS Church's genealogy website, and also on

subscription services like Ancestry. Chances are, you have

information about someone who was alive in the U.S. in 1950; if you can find them in the census (and

knowing their date of birth from the SSDI will help), you will find their parents, siblings, children, and

maybe even grandparents. Census records can give you names, family relationships, age, place of birth,

occupation, year of immigration, an approximate date of marriage, and other things. Of course, the

information is only as accurate as the knowledge of the person interviewed and the person's ability to

communicate with the census taker, but if you get several years of census records, a consensus will develop.

- Remember that names can change over time. You may need to use some creativity in searching. It helps to

keep track of the names and ages of everyone in the household, siblings as well as direct ancestors. There

may be several Harry Brodskys in the census, but how many of them have twin children named Samuel and

Beatrice? If you have trouble finding someone, try assuming that one of the facts you know is wrong. Can't

find the right Harry Brodsky? Try just searching for just Brodsky with his year and place of birth, or just

Harry with his year and place of birth. Also try assuming that part of the surname (usually the end) may have

been cut off. For example, Harry's brother William changed his surname to Brod.

- 4. Birth, Marriage and Death Records

- If your ancestors lived in New York City (and many Jewish ancestors did), the

Italian Genealogical Group has created incredible databases

indexing New York City birth, marriage and death records. They do not have any of the actual records, but it

will give you precise dates if you don't know them (or confirm dates if you do know them). The marriage index

can also get you the bride's maiden name (search for the groom, click the link to the bride, and it will have

her maiden name).

- The index also gives you the certificate numbers, which allow you to order a copy of the original

certificate from the New York

Municipal Archives. It's not free (about $15 per certificate), but I think it's worth every penny. New

York marriage records contain the names of the parents of both bride and groom, including maiden names: four

additional names that you may not have had, a whole generation of ancestors who may never have come to

America. Death records also have parents' names, though of course this would only be two parents, and the

accuracy of the information is only as good as the knowledge of the informant. Birth records give the

mother's maiden name.

- You may also find useful information in birth, marriage and death notices in the newspaper. In addition

to the date of birth, marriage or death, these notices may give you the names of relatives. The parents of

the child, bride or groom are routinely mentioned in birth and marriage notices; the names of surviving

parents, siblings or children are commonly mentioned in death notices. The age of the decedent is also

commonly mentioned in death notices, which gives an approximate date of birth.

Legacy.com is an excellent source for obituaries since about

2000. If your ancestors lived in a city with a large Jewish community, the notices may be included in the

local Jewish paper, like Philadelphia's Jewish Exponent (some

of which is indexed by JewishGen), Columbus's

Ohio Jewish Chronicle,

Cleveland

Jewish News, or

Pittsburgh's

Jewish newspapers. If your ancestors lived in New York, these notices may be available in the New York

Times, which has an excellent archive search tool for anything

dating back to 1851. Some other newspapers also have their B/M/D notices searchable online. Ancestry has

birth, marriage and death announcements from the NYT and a few other newspapers from 1851 to 2003, but their

index of those notices is atrocious. Other good sources of news items are

GenealogyBank or

Newspapers, which which have outstanding collections of local

newspapers, but they are not free. These sources have very different collections.

- 5. Immigration and Naturalization Records

- Early immigration records (before 1900 or so) don't have much information, but later ones can tell you a

lot of useful things. Ellis Island has a free search tool for

their records, but you may be surprised to learn that not everybody came through Ellis Island! Ellis Island

opened in 1892, so if your ancestor came over before that time, you'll have to look elsewhere. Earlier

immigrants to New York came through Castle Garden, but their website is no longer online. You can search

their records (and Ellis Island's!) free on

FamilySearch. Other Jewish immigrants

came through Philadelphia, Baltimore or other ports that do not have comprehensive search tools freely

available. Many of these records can be found through subscription services like

Ancestry.

- Early naturalization records (before 1900 or so) do not contain much information, but later

naturalization records contain one of the most valuable pieces of information, and one of the hardest to

find: the town of birth overseas. Most other kinds of records simply give the country of birth, which may not

be very useful because of frequent border changes. Naturalization records are supposed to have the town of

birth (though my great-uncle put his "town" of birth as Bessarabia, a country). Many naturalization records

can be found on Ancestry.

- 5. Overseas Records

- If you've gotten this far, you may be ready to start looking for your immigrant ancestors in their

country of origin. JewishGen has transcribed an enormous number of

specifically Jewish records, both from overseas and from the United States. Their searches include a special

Soundex (sounds like) strategy that takes into account the longer names that are common among Jews and the

pronunciations of Jewish names. The site is organized by country of origin, but the creators of the site have

FINALLY created a Unified Search that cuts across all

borders so you don't need to know the precise country of origin. If your ancestor came from "Russia," this

search will include Belarus, Latvia, Lithuania and Ukraine, no more need to search them all one at a time.

You will need a free registration to look at the transcribed records. An annual donation to JewishGen will

give you enhanced search capabilities.

- If your ancestors are from Vienna, GenTeam.at (free with

registration) has an excellent and growing collection of Austrian records, most notably an index to the

Vienna Matrikel (Jewish register of births, marriages and deaths). The information transcribed is incomplete,

but most of the Vienna Matrikel is available on microfilm from the LDS Church (see below), and this index

will help you find out what records might be on those microfilms. I found dozens of useful records here.

- The LDS Church has an increasing number of overseas records available on their

Family Search website, so you may want to check that out too.

Many of the overseas records they have are just browsable images, with no index, but their indexes are

growing. You used to be able to borrow these microfilms to your local LDS church but I'm not sure if that is

possible any more. You can find the microfilms and see if they are indexed or scanned and browseable in their

catalog. Here is how you find Jewish records in

their catalog:

- Search by Place. Use the most specific place you know, preferably a town name. Enter it in the original

language: for example, enter Wien, not Vienna. If you use the English name, it will cross-reference you. If

you know of multiple names for the town, check each one. Click the correct town name in the list of matches

that appears.

- If you don't find the specific town, try searching for the name of a broader area, like the county or

district

- You will see a list of topics. Ideally, you want to find the topic Jewish Records. If there is no Jewish

Records topic, look for a Civil Registration or a Vital Records topic. In Germany and some other European

countries, Jews were included in the same registries as gentiles. Click the topic.

- If you don't find any Jewish records in the specific town, try changing to a broader area taking out the

town name, leaving only the country and district.

- You will see a list of titles that match the topic. Click the title for more information.

- Scroll down to the Notes section. If there is a searchable index for the title, it will tell you

that it's available in bright red letters with a link to the index, but be aware: that index may not be

complete!

- If there is no link to an index, or if the search doesn't get what you are looking for, scroll down to

Film/Digital Notes to see a list of each microfilm. You may need some help from Google Translate to

know what each film holds because they are written in the native language! Then click the camera icon in the

column on the right to see the microfilm's images.

- 6. Other Record Types

- Of course, there are many other kinds of records that may contain interesting or useful information. For

example, I have gotten a lot of useful information from WWI and WWII draft registration and enlistment

records on Ancestry. These records tell where and when the person was

born (sometimes giving the city), whether the person was married (which can help you narrow down the date

when your ancestor married), and have other useful information. The mere existence of a registration can

confirm that a person was still living in 1942, which is not always easy to deetermine. The WWII draft

registration on Ancestry is the "Old Man's Registration," which has men born between 1877 and 1897, which

often includes your immigrant ancestors, and it includes the town of birth, which may be hard to find

elsewhere.

- Travel records from Ancestry's ship manifests collection can also be helpful in determining the date a

person was born or married. Older travel records often included a person's marital status, address and date

of birth. You may even be able to find your ancestor's passport on Ancestry, which sometimes contains a

photograph.

☰ Translation of Foreign Genealogical Terms

Here are some useful genealogical terms in German and Hungarian, which are the

languages of most of the records I have worked with. You may find these terms

as column headings in metrical books, the most commonly available source of

foreign Jewish records. For additional translations and additional languages,

try Google Translate.

| English |

German |

Hungarian |

|

Name

|

Namen

|

Neve

|

|

Age

|

Alt

|

Kora, Életkora

|

|

Date

|

Datum

|

Keltje, Ideje

|

|

Year

|

Jahr

|

Év

|

|

Month

|

Monat

|

Hó, Hónap

|

|

Day

|

Tag

|

Nap

|

|

Birth

|

Geburt

|

Születési

|

|

Child

|

Kind

|

Gyermek

|

|

Father

|

Vater

|

Atya

|

|

Mother

|

Mutter

|

Anya

|

|

Parents

|

Eltern

|

Szüleinek, Szülõk

|

|

Marriage

|

Heiraten, Trauung

|

Házasok, Esketési

|

|

Bride

|

Braut

|

Mátka

|

|

Groom

|

Bräutigam

|

Völegény

|

|

Death

|

Sterbens, Tod

|

Halálozás

|

|

Decedent

|

Verstorbenen

|

Halott

|

☰ DNA Testing and the Ashkenazi Problem

DNA testing has become increasingly popular for genealogy purposes, but it is

difficult for Jews to get useful results from DNA testing because Jews are an

endogamous group. Jews tend to marry Jews, and Jews who do not marry Jews tend

to drop out of the Jewish community, and we have been doing that for so long in

such a small population that we all tend to have a lot of DNA in common. This

is sometimes referred to as the

Ashkenazi Problem. As a result, Jews

will match more than half of all Jews who have had a DNA test.

It is still possible to successfully make genealogical connections using DNA

testing, but it may require more work than you expect, and may require a lot of

research to confirm that your matches are actual relatives. If your family has

been separated by the Holocaust or by adoption, DNA testing may be the only way

to find the missing leaves on your tree.

For more information, see the

blog

post I wrote for DNA Day 2017.

☰ Jewish and General Genealogy Resources

Here are links to some sites I have found useful for Jewish genealogy:

- JewishGen: THE site for

Jewish genealogy, with a wealth of transcribed Jewish records (both American

and European) and lots of useful advice and information

- Avotaynu: A Jewish genealogy

newsletter and publisher, creating many useful books to help with your

research.

- Italian Genealogy Group: Not a

specifically Jewish source, obviously, but their extensive indexes of New York

City birth, marriage, death and naturalization records, all available for free,

are extremely valuable to Jewish researchers, who often have ancestors in New

York

- Ellis Island and Castle Garden: The two primary ports

of immigration, can be searched at FamilySearch for free

- FamilySearch: The LDS church

is working on putting all of their enormous collection of genealogical

microfilms online for free. For example, they have images of Philadelphia

marriage indexes and death records, which are not available anywhere else

online. Registration is required to view the actual records in some cases.

- Ancestry: The largest genealogical

source on the web. They don't have much that is specifically of interest to

Jewish researchers (except the material that they obtained from JewishGen), but

they have an enormous amount of American material that will get you from the

present day back to your immigrant ancestors, and their immigration records.

This is a subscription service, and a rather expensive one, so you'll want to

do as much as you can for free before you try it, and you may want to start

with one of their short-term

free trial

subscriptions

- Stephen Morse's One Step Portal: A

wealth of tools that make it easier to locate records in many of the sources of

interest to Jews. He doesn't have any records of his own; he merely provides

enhanced searching capabilities for other websites that exist, including both

free websites and subscription sites

- Several New York area Jewish cemeteries have online interment searches,

including:

Mount

Ararat,

Mount

Carmel, Mount Hebron,

Mount Judah,

Mount Lebanon, and

Mount Zion. This will

give you an approximate date of death (assume death was within a week before

burial, unless the body was moved). You may also find other possible family

members by searching for the location of the graves: family members may be

buried together. There are also sites for some cemeteries in the Philadelphia

area with interment searches

(Montefiore,

Mt. Sinai), general

resources for interment searching (Find A

Grave).

- Fold3, formerly known as Footnote:

This used to be a general source of American records, but was bought out by

Ancestry.com and changed its focus to military records. Its non-military

information is now available in Ancestry. I'm not sure I would recommend this

any more, unless you have a specific interest in military records.

I have also used the genealogy site My

Heritage, though I didn't find much there that wasn't available in other

sources. Your experience may vary.

During

the Holocaust, the Nazis killed people, burned synagogues and wiped out towns,

but they did not destroy records. Quite the contrary, they carefully preserved

synagogue records of births, deaths and marriages back to the 1840s... so they

could identify Jews for extermination. See this puzzling stamp, dated November

30, 1940, on my great-grandfather's 1878 Vienna Jewish birth record: Annahme

des Zusatznamens Israel-Sara angezeigt (assume of the other names that

Jew-Jewess is indicated). What is the meaning of this cryptic message? It is a

reminder to those inspecting the records that they should assume everyone

mentioned on the page is Jewish -- not just the parents and children, but also

the rabbi,

mohel, midwife, witnesses, and so forth.

Many of these European records, diligently preserved by the Nazis, are indexed

by JewishGen

or are available from the Family

History Library of the Latter Day Saints (Mormons). Both of these resources

are discussed below.

During

the Holocaust, the Nazis killed people, burned synagogues and wiped out towns,

but they did not destroy records. Quite the contrary, they carefully preserved

synagogue records of births, deaths and marriages back to the 1840s... so they

could identify Jews for extermination. See this puzzling stamp, dated November

30, 1940, on my great-grandfather's 1878 Vienna Jewish birth record: Annahme

des Zusatznamens Israel-Sara angezeigt (assume of the other names that

Jew-Jewess is indicated). What is the meaning of this cryptic message? It is a

reminder to those inspecting the records that they should assume everyone

mentioned on the page is Jewish -- not just the parents and children, but also

the rabbi,

mohel, midwife, witnesses, and so forth.

Many of these European records, diligently preserved by the Nazis, are indexed

by JewishGen

or are available from the Family

History Library of the Latter Day Saints (Mormons). Both of these resources

are discussed below.  Jewish Names

Jewish Names