Level: Basic

Ashkenazic and Sephardic Jews represent two distinct subcultures of Judaism. We are all Jews and share the same basic beliefs, but there are some variations in culture and practice. It's not clear when the split began, but it has existed for more than a thousand years, because around the year 1000 C.E., Rabbi Gershom ben Judah issued an edict against polygamy that was accepted by Ashkenazim but not by Sephardim.

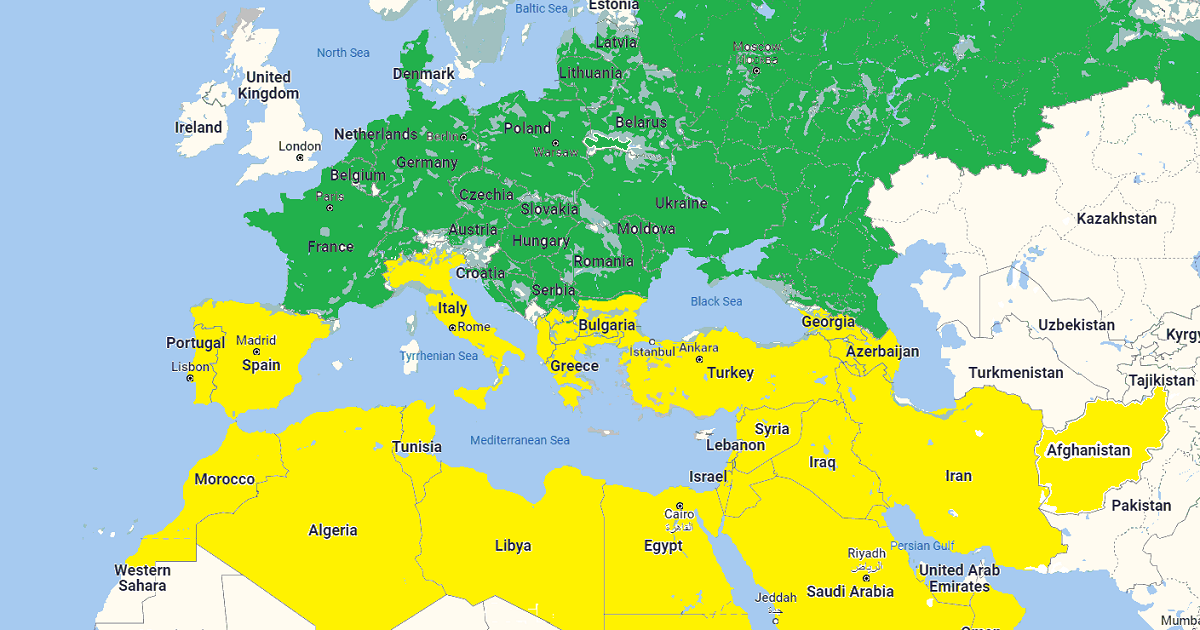

Ashkenazic Jews are the Jews of France, Germany, and Eastern Europe and their descendants. The adjective "Ashkenazic" and corresponding nouns, Ashkenazi (singular) and Ashkenazim (plural) are derived from the Hebrew word "Ashkenaz," which is used to refer to Germany. Most American Jews today are Ashkenazim, descended from Jews who emigrated from Germany and Eastern Europe from the mid 1800s to the early 1900s. The pages in this site are written from the Ashkenazic Jewish perspective.

Sephardic Jews are the Jews of Spain, Portugal, North Africa and the Middle East and their descendants. The adjective "Sephardic" and corresponding nouns Sephardi (singular) and Sephardim (plural) are derived from the Hebrew word "Sepharad," which refers to Spain.

Sephardic Jews are often subdivided into Sephardim, from Spain and Portugal, and Mizrachim, from the Northern Africa and the Middle East. The word "Mizrachi" comes from the Hebrew word for Eastern. There is much overlap between the Sephardim and Mizrachim. Until the 1400s, the Iberian Peninsula, North Africa and the Middle East were all controlled by Muslims, who generally allowed Jews to move freely throughout the region. It was under this relatively benevolent rule that Sephardic Judaism developed. When the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, many of them were absorbed into existing Mizrachi communities in Northern Africa and the Middle East.

Most of the early Jewish settlers of North America were Sephardic. The first Jewish congregation in North America, Shearith Israel, founded in what is now New York in 1684, was Sephardic and is still active. Philadelphia's first Jewish congregation, Congregation Mikveh Israel, founded in 1740, was also a Sephardic one, and is also still active.

In Israel today, a little more than half of all Jews are Mizrachim, descended from Jews who have been in the land since ancient times or who were forced out of Arab countries after Israel was founded. Most of the rest are Ashkenazic, descended from Jews who came to the Holy Land (then controlled by the Ottoman Turks) instead of the United States in the late 1800s, or from Holocaust survivors, or from other immigrants who came at various times. About 1% of the Israeli population are the black Ethiopian Jews who fled during the brutal Ethiopian famine in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The Ethiopian immigration continues on a smaller scale to the present day, with Operation Tzur Israel bringing 2,000 Ethiopian Jews to Israel in 2021 and another wave stalled in 2022.

The beliefs of Sephardic Judaism are basically in accord with those of Orthodox Judaism, though Sephardic interpretations of halakhah (Jewish Law) are somewhat different than Ashkenazic ones. The best-known of these differences relates to the holiday of Pesach (Passover): Sephardic Jews may eat rice, corn, peanuts and beans during this holiday, while Ashkenazic Jews avoid them. Although some individual Sephardic Jews are less observant than others, and some individuals do not agree with all of the beliefs of traditional Judaism, there is no formal, organized differentiation into movements as there is in Ashkenazic Judaism.

Historically, Sephardic Jews have been more integrated into the local non-Jewish culture than Ashkenazic Jews. In the Christian lands where Ashkenazic Judaism flourished, the tension between Christians and Jews was great, and Jews tended to be isolated from their non-Jewish neighbors, either voluntarily or involuntarily. In the Islamic lands where Sephardic Judaism developed, there was less segregation and oppression. Sephardic Jewish thought and culture was strongly influenced by Arabic and Greek philosophy and science.

Sephardic Jews have a different pronunciation of a few Hebrew vowels and one Hebrew consonant, though most Ashkenazim are adopting Sephardic pronunciation now because it is the pronunciation used in Israel. See Hebrew Alphabet. Sephardic prayer services are somewhat different from Ashkenazic ones, and Sephardim use different melodies in their services. Sephardic Jews also have different holiday customs and different traditional foods. For example, both Ashkenazim and Sephardim celebrate Chanukah by eating fried foods to remember the miracle of the oil, but Ashkenazim eat latkes (potato pancakes) while Sephardim eat sufganiot (jelly doughnuts).

The Yiddish language, which many people think of as the international language of Judaism, is really the language of Ashkenazic Jews. Sephardic Jews have their own international language: Ladino, which was based on Spanish and Hebrew in the same way that Yiddish was based on German and Hebrew.

There are some Jews who do not fit into this Ashkenazic/Sephardic distinction. Yemenite Jews, Ethiopian Jews (also known as Beta Israel and sometimes called Falashas), and Asian Jews also have some distinct customs and traditions. These groups, however, are relatively small and virtually unknown in America. For more information on Ethiopian Jewry, see the North American Conference on Ethiopian Jewry or Friends of Ethiopian Jews. For more information on Asian Jewry, see Jewish Asia.